Read our booklet to learn all about this issue

Click chapters below to open

-

0

Cover: Disappearing Beauty -

1

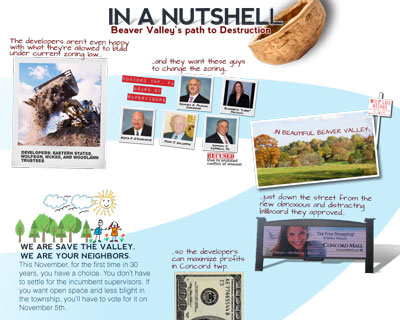

The Story in a Nutshell -

2

Beauties of the Valley -

3

Green Space in Concord -

4

Development Plans -

5

Impacts of failure -

6

The Woodlawn Trustees -

7

Decision Makers -

8

Public Resistance -

L

Library of additional resources

Photo by Jim Graham courtesy The Conservation Fund

This is a long and complicated story. There's no getting around it. It's important, however, that our supporters understand the whole story because this is not your typical land deal and development proposal. We've assembled this story into a clear, nine chapter digest that is easy to read. This first chapter gives an overview of the whole issue. Subsequent chapters delve more deeply into each topic. The last chapter is full of additional resources that allow you to explore deeper on your own.

Just west of route 202 on the Pennsylvania/Delaware border lies a hidden gem in the midst of big box retail stores and urban sprawl. This area is known by locals as "The Valley", but formally as Beaver Valley. Beaver Valley consists of thousands of acres of woodland and farmland and is treasured for its rare beauties, historic and ecologic significance, and offers an incredible recreational wonderland for hikers, bikers, horseback riders, and runners.

Members from all walks of life have joined together to help preserve over 750 acres of pristine land in beautiful Beaver Valley that is currently slated for development. This movement was started by two separate organizations, Save The Valley, and The Beaver Valley Conservancy, with a common goal, to save Beaver Valley from development.

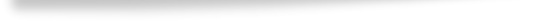

Slightly more than half of the Valley’s lands are included within the newly-designated First State

National Monument and permanently protected. Another 15% or so are held by individuals and

operated as farms or country places. Some of these privately owned properties are permanently

protected with conservation easements; others are expected to be so protected in the near future.

The final 771 acres are owned by Woodlawn Trustees, Incorporated, a Delaware corporation.

Of these 771 acres, approximately 60% (447 acres) lie in New Castle County, Delaware; the remaining

40% (324 acres) in Concord Township Pennsylvania. All adjoin, the First State National Monument and

Brandywine Creek State Park.

Don't let the name fool you, the Woodlawn Trustees are not stewards of the land. They want to sell the land to three other development companies.

Instead of selling the land to a consortium of preservation organizations, the Woodlawn Trustees are selling their land to developers who are attempting to change the zoning laws so that they can build almost ten times what they're legally allowed to.

They are not even satisfied with what they can build by law.

Thousands of citizens are uniting in an attempt to defend and protect this land that is so meaningful to the community.

We are currently focusing our efforts on the 324 acres in Concord Twp because that is most immediately at risk.

On the northern edge of nearly 2,300 acres of permanently preserved and protected lands, in

close proximity to another 2000 or so acres of privately owned and permanently protected land,

and located in a small area where most individual landowners use their lands consistently with

good conservation and preservation practices, Beaver Valley including the Woodlawn land

proposed for development provide nearly unmatched habitat for Mid-Atlantic Piedmont flora

and fauna, and in the stone and frame 18th and 19th century dwellings and outbuildings – barns,

corn cribs, cart sheds, and springhouses - that dot the landscape, an induplicable evocation of

our regional rural heritage. Crisscrossed with miles of trails, the Valley offers an incredible

recreational wonderland for bikers, hikers and horseback riders.

The importance of these lands has been recognized by New Castle County, which has

recommended that the Delaware roadways that wind through them be designated National

Scenic Highways, by the Delaware County Planning Commissions which has encouraged their

preservation and protection, and by the United States; which designated a portion of them as

a National Monument in early 2013. Their haunting and magical character was effectively

captured by the National Geographic in March, 2013, when it described them as existing “at

some indeterminate point in time…somewhere between the 18th and the 20th centuries.”

In the wake of Woodlawn’s apparent decision to monetize its “country properties” by developing

them, this fragile eco-system, historical treasure trove, and recreational wonderland is threatened.

Although many have urged Woodlawn to do otherwise, its current plans are to sell the 325

acres located in Pennsylvania to developers instead of offering them to those who would protect

them or working with local organizations to that end.

However, the development companies cannot build as planned because the law only allows a fraction of what is proposed. The developers have submitted a "rezoning proposal" in order to accommodate their proposed development. In other words, they are submitting a request to change the law in order to allow for an enormous increase in development so they can maximize their profits.

Proposed are 3 large residential developments (400-500+ houses) and a massive quarter-million square foot commercial complex including a nationally opposed big box retail store.

The decision makers in charge of either accepting or rejecting this proposal are the five members on the Concord Township board of supervisors. More about them in chapter 7.

In response, in a movement that was started by two separate organizations, Save the Valley

and the Beaver Valley Conservancy, with a common goal of saving Beaver Valley from

development, thousands of citizens.

In response, in a movement that was started by two separate organizations, Save the Valley

and the Beaver Valley Conservancy, with a common goal of saving Beaver Valley from

development, thousands of citizens.

Our primary goal is to block the rezoning proposal in Concord Township, then have the land purchased by a consortium of preservationist organizations where it can ultimately be donated to the federal government, the state parks system, or a conservancy organization with a land easement in place.

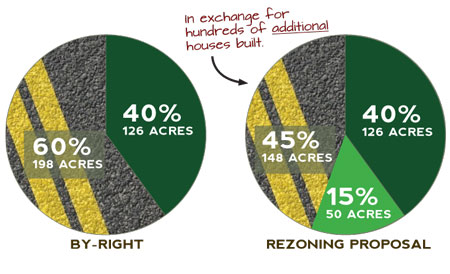

It's a complicated issue, but it can be boiled down to the graphic on the right. The developers aren't happy with what they can build in Beaver Valley under current zoning law so they want the Concord Board of Supervisors to change the zoning so the developers can maximize profits.

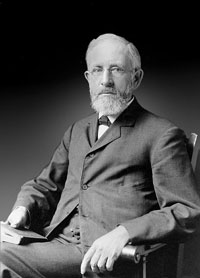

Around the turn of the 20th century, William Bancroft, a wealthy philanthropist from Wilmington, saw how the city was spreading beyond its borders and formed a plan to protect as much of the surrounding countryside as he could for future generations.

He wanted in his own words, "to gather up the rough land along the Brandywine Creek above Rockland and hold it for the future Wilmington, a Wilmington of hundreds of thousands of people." As he said, "It has been a hobby, or a concern with me, for more than twenty-six years, to endeavor to get park land for the advantage of the people of Wilmington and its vicinity." Wanting his work to continue on after him, Bancroft formed Woodlawn, an incorporated entity charged in part with the task of protecting the lands he had secured. And for a while, the Woodlawn Trust fulfilled Bancroft's vision.

In the woods and meadows of Beaver Valley exists some of the last unspoiled bucolic scenery in Delaware County. In an area bounded by Smithbridge Road and Route 202 and bisected by Beaver Valley Road, hikers and riders of bikes and horses skirt the edges of forests in which Native Americans lived, pass by historic barns and houses that were built when the founding fathers of this country were still alive, cross meadows teeming with wildlife, ford shallow creeks which leak from ancient springs in the hills of Delaware County and Northern Delaware.

As our cities have sprawled to engulf the country-side around them, conservationists, cultural

analysts, and politicians have become increasingly aware of the importance of “large landscapes”

in providing a stabilizing anchor in a rapidly changing world, a context for our national existence

and culture, and in contributing to our collective mental and physical health. The recently

adopted Presidential “Great Outdoors Initiative” focuses in part on the importance of preserving

such landscapes. Beaver Valley and the lands that adjoin it is among the last large landscapes

around.

Increasingly an island in a sea of suburban development, Beaver Valley is something of an

ecological miracle. Its woodlands – of native tulip poplar, beech, red and white oak, cherry,

and walnut – are the most extensive in Delaware County and among the most mature anywhere

in Southeastern Pennsylvania – 75 (and in some case more than 100 years) along the long

process of reversion to native forest.

The Valley also is a critical part of the Brandywine and Delaware River watersheds.

Remarkably, at least one of its creeks remains cold enough and pure enough to hold a small

population of trout, at the extreme southern edge of their range. The open wetlands and

woodland borders provide extensive habitat for the one of the world’s ten most endangered

species, the bog turtle.

At least four species native plants that are classified as “of concern” thrive in the valley’s

meadows and woods. At the very edge of the properties proposed to be developed stands at least

one documented American chestnut. Eagles nesting on the Brandywine regularly visit the Valley

to hunt its open meadows and fields; a breeding pair of red tailed hawks resides there.

At least four species native plants that are classified as “of concern” thrive in the valley’s

meadows and woods. At the very edge of the properties proposed to be developed stands at least

one documented American chestnut. Eagles nesting on the Brandywine regularly visit the Valley

to hunt its open meadows and fields; a breeding pair of red tailed hawks resides there.

In short, the Valley’s ecosystem is a survivor, slowly healing itself from 200 years of farming

and milling. However, it remains an embattled survivor. With every substantial rain, Beaver

Creek now overflows with runoff from the developments across 202, carrying with it oils,

chemicals, and other pollutants. The once teeming population of minnows, salamanders, and

crawfish that supported a feral population of mink, gone wild from a failed ranching experiment,

a native population of weasels, and far more substantial populations of skunk and raccoons

than exist today, the creek too warm to support them. Likewise, Beaver Valley, is a relatively

diminutive survivor. As ecological study after study has shown, small parcels of land isolated

from similar open space cannot support a diversity of plant and wildlife. In short, while the

Valley currently supports an astonishing diversity of wildlife and native flora, it cannot afford

to shrink. Likewise, while the Valley benefits exponentially from its contiguity with relatively

large expanses of other protected lands, even its partial destruction will adversely affect all of

those other lands.

This valley is truly magical, and surely not just a natural treasure, but an historical one as well. George Washington's Continental Army camped nearby and legend has it that British troops commandeered supplies in Beaver Valley. Located less than 2 miles from the famous Brandywine Battlefield, the Delaware County Planning Commission said that the area has "high potential" for archaeological resources given that it has remained undeveloped since the Township's founding before 1683. In addition, there are intact historic structures, some of which date to the early 19th century, and the remains of many historic structures, all of which developers plan to bulldoze. On this land are a host of wildlife including bald eagles, owls, hawks, fox, deer, raccoons, skinks, turtles, birds and more, even including a world-wide endangered and protected species.

Before the Valley was settled by Europeans, it was traversed by Lenni Lenape, traveling by

means of a still undiscovered path from their summer camp at the “Big Bend” of the Brandywine

River to Naaman’s Creek – pausing at Beaver Valley Cave to seek rest and shelter, to store

produce and supplies.

Before the Valley was settled by Europeans, it was traversed by Lenni Lenape, traveling by

means of a still undiscovered path from their summer camp at the “Big Bend” of the Brandywine

River to Naaman’s Creek – pausing at Beaver Valley Cave to seek rest and shelter, to store

produce and supplies.

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Valley’s lands were taken up by Europeans, many

Quaker, many coming with William Penn in pursuit of their personal peaceable kingdoms.

The lands were cleared, surveyed, and domesticated into the dispersed family farms that

characterized settlement patterns in the region. These farms were “mixed” farms – producing

a variety of products (especially grain) for home use, and export to Colonial America’s largest

city, Philadelphia, and from there to Europe and the West Indies. Conestoga Wagons rumbled

by on the “great road” (today, 202), enroute to mills and ports, including those in the new town

of Wilmington, stopping for rest and refreshment at the taverns that stood at each intersection

of Beaver Valley and the Great Road – The Nine Ton in Pennsylvania and another in

Delaware.

During these years, the Valley even played a role in one of the darker moments of the American

Revelation, as British troops raided it for supplies – riding off, according to family history, with

Robert Green’s best mare, as he continued to plow.

As the 18th century waned, agriculture began to change. Butter replaced grain as the most

important commercial product, transforming and elevating the economic place of rural women.

Later in the century, the production of milk products for urban markets replaced butter as the

Valley’s most valuable agricultural product.

Mills in The Valley

A stray reference to Beaver Valley in 1694 refers to the lands bordering Beaver Creek as “mill

lands,” and surveyors laying out Beaver Valley Road in 1712 passed by “the mill that Chandler

is building”. Until well into the 19th century, Beaver Creek and its tributaries supported small

mills – generally managed by their owners and from one to three workers that produced a range

of products, from lumber, to tin, to flax, to paper. By the third quarter of the 19th century the

Valley had become a thriving community of several hundred people organized around two

schools, the mills, and the characteristic family farms of 40 to 120 acres.

The land wasn’t good enough, the farms weren’t big enough, and the power supplied by

Beaver Creek wasn’t strong enough for this economy and society to survive the economic and

technological changes of the last half of the 19th and the first years of the 20th. One by one,

the mills closed, the last (then an axe handle factory) about 1940. One by one, the farms were

purchased by Woodlawn. But, much of the evidence of these worlds we have lost is still there:

partly, in the stone and frame houses, barns, spring houses, and cart sheds that dot the landscape;

partly, in the stone walls that now wander through woodlands quietly memorializing ancient

property boundaries and fields; and partly in the abundant archaeological evidence of early

occupation and land use that is scattered across the landscape, just waiting to be documented

and interpreted. Delaware County has identified these lands as have having high potential for

archaeological resources. On those that would be developed, these resources will be destroyed

along with most of the standing historical buildings.

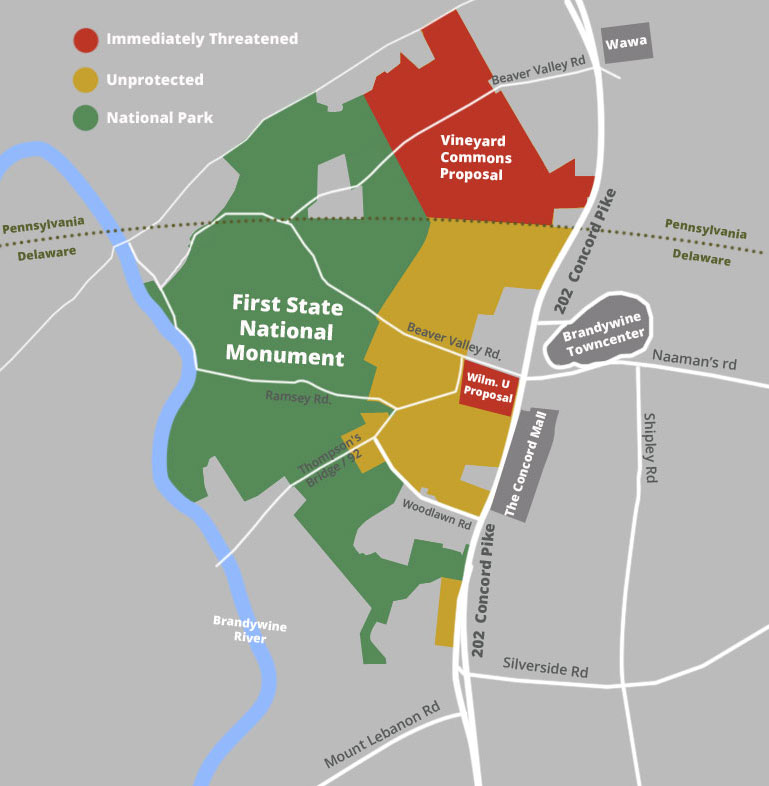

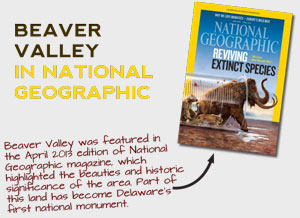

In April of 2013 about half of the Valley’s lands were designated a National Monument under

the Antiquities Act of 1906. In supporting that designation, the United States Department of the

Interior identified several factors that justified the elevation of the Valley’s lands to the same

legal status as Mount Vernon and the Statute of Liberty: the importance of the evidence of early

settlement patterns that it contains; its geological and ecological significance; and the role of

its lands as an emblem of 20th century conservation, and prescient, intelligent land planning.

But what makes the Woodlawn land so famous is its intricate network of trails that is used by hundreds every day. Woodlawn even touts its large trail system on their website.

In April of 2013, a large portion of the Woodlawn trust was purchased, funded by the Mount Cuba Foundation, a preservation organization in Wilmington, and then donated to the federal government to be preserved in perpetuity.

That very month, Beaver Valley was featured in National Geographic Magazine, which highlighted its beauties and rich history.

The 325 acres that are proposed to be developed are identical

in all material respects to those lands that were included in the National Monument.

If the latter are worth saving, so are these.

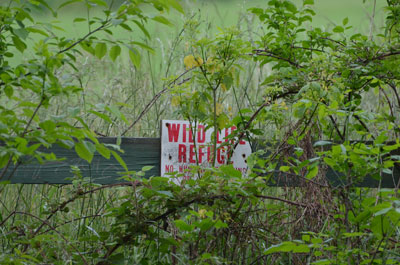

Now, that very land is on the brink of destruction. In the past, thousands of acres in Beaver Valley have been carefully protected by Woodlawn Trustees as a wildlife refuge but over the last 60 years Woodlawn has been slowly selling off William Bancroft's legacy to developers, slowly perverting his dream of a greenway flowing north out Wilmington.

Of the 5,800 acres Woodlawn has acquired in its existence, they have sold 2,900 acres to developers. Their website claims that the new National Monument land consisting of 1,100 acres was a gift by Woodlawn to the federal government when in fact the parcel was actually sold to the Mount Cuba Conservation Trust for $20 million, which was in turn donated to the federal government. In the 80 plus years of its existence, Woodlawn has given away precious little of its total land to conservation, and the majority sold to housing development projects and commercial retail lots. Now just 771 acres remain of the original 5,800, and rather than protect it, Woodlawn plans to sell it to developers, just like it has done in the past.

Of the 5,800 acres Woodlawn has acquired in its existence, they have sold 2,900 acres to developers. Their website claims that the new National Monument land consisting of 1,100 acres was a gift by Woodlawn to the federal government when in fact the parcel was actually sold to the Mount Cuba Conservation Trust for $20 million, which was in turn donated to the federal government. In the 80 plus years of its existence, Woodlawn has given away precious little of its total land to conservation, and the majority sold to housing development projects and commercial retail lots. Now just 771 acres remain of the original 5,800, and rather than protect it, Woodlawn plans to sell it to developers, just like it has done in the past.

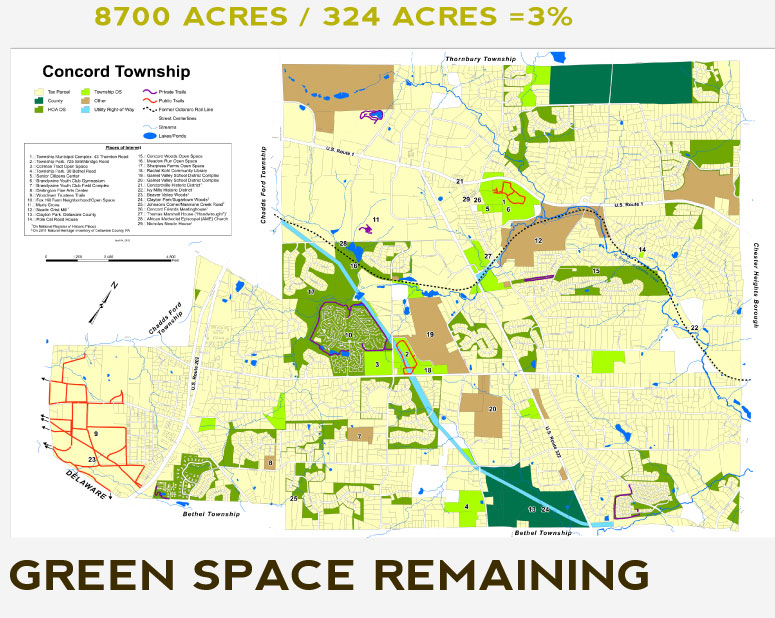

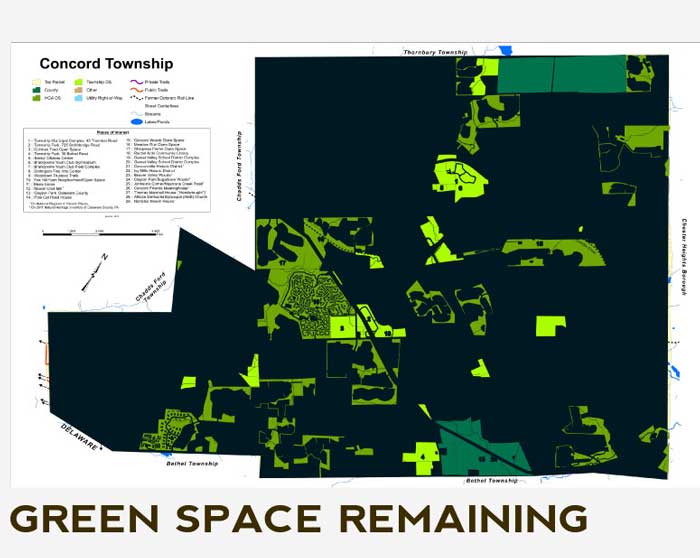

Concord has a history of touting green space that's not really green space.

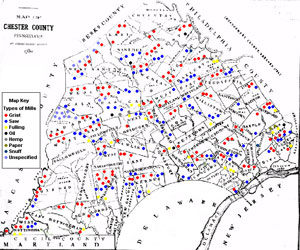

Click an image to zoom in

A modest attempt to set aside open space in the township provided residents some unspoiled land to use in common. However, a large percentage of "open space" in Concord is inaccessible, or fenced in, or lies in a utility right of way, or constitutes a very narrow ring of green-space around densely constructed developments. True open space, which many in Concord see now as something to protect not pave over, is almost completely gone, except for the Woodlawn parcel at the south western edge of the township, a parcel which the Concord Township website features as a feather in their cap because of its trails and history. How can a township tout open space and the Woodlawn Trust's trails and then take no action to protect it? If the supervisors vote to permit any construction on this land, they are killing the thing that people love most about Concord Township.

Take a look at the map (above) of green space in Concord township. At a glance it looks like Concord has done an excellent job in creating green space for the public good, but a closer examination shows that this is not true at all. Most of the land presented as "open space" is not true open space. In some cases, they count the tiny lawn areas in between houses in a dense housing development as open space. Is this a joke or a lame attempt at meeting the open space requirements of the township?

"Open Space" is a much used term by both sides in the fight over Beaver Valley. Given the vastly different ideas of what that term means, it is important to describe how Save The Valley's idea of open space compares with the supervisors, the developers, and Woodlawn.

Open space, for us, constitutes a large, uninterrupted tract of rich land most closely resembling its natural state. In addition to providing ample habitat and food sources for a large, diverse population of wildlife, it is a filter that helps keep streams pure. It offers outdoor recreational opportunities in an unspoiled place. It not only provides residents in the area with a nearly pristine view shed, it can support farmers as well. In short, open space is beautiful and extremely useful, but difficult to appraise in dollars and cents.

Open space for the Concord supervisors, developers, and Woodlawn is a very different concept indeed. For them, open space can have power lines over it, be a playing field, or consist of a drainage basin, or a strip of grass along a road. For them, it can fall within the fenced-in area of a commercial operation, or trapped within the perimeter of a development, unusable to everyone and off limits to anyone who doesn't live in those homes. Their open space contains no old trees and is stripped of its most natural qualities. It supports virtually no wildlife, as there is no food anywhere for them to eat. It is most likely treated with landscape chemicals, and is not much of a buffer against the contamination of our streams and rivers. If it has hiking trails, they're most likely paved with asphalt or lie under power lines or in the midst of a dense neighborhood. In short, open space to them is just a piece of sterile land colored green that represents unrealized profits.

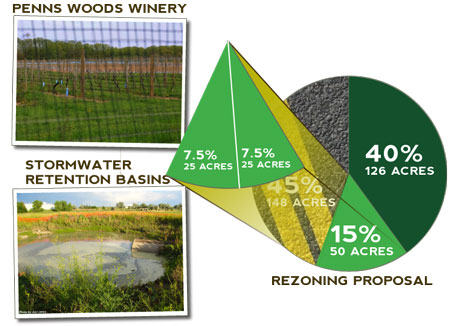

We are not exaggerating. The sterilized open space proposed by the developers and Woodlawn falls almost completely within the boundary of the development, and they begrudge us even that. The ridiculousness of their position can be clearly understood by considering the other areas that they have offered or are required to keep "open": wetlands, areas of steep slope, storm water basins, and a vineyard with a fence around it. A storm water basin is their idea of a wetland, and a forest for them is a line of trees purchased at a nursery and constituting a monoculture. A real wetland to them is an impediment to construction, not a cornucopia of wildlife and a natural pollution filter that buffers against flooding. To them, a real forest is a fungible commodity, not a great place to hike.

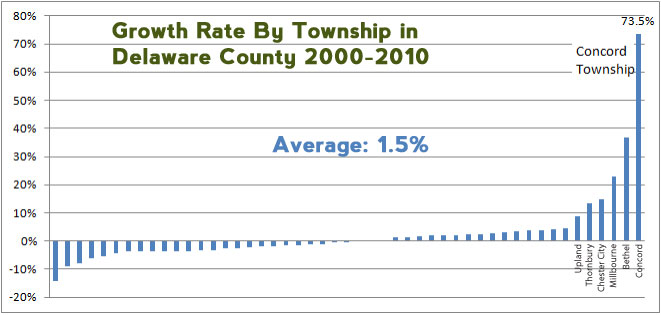

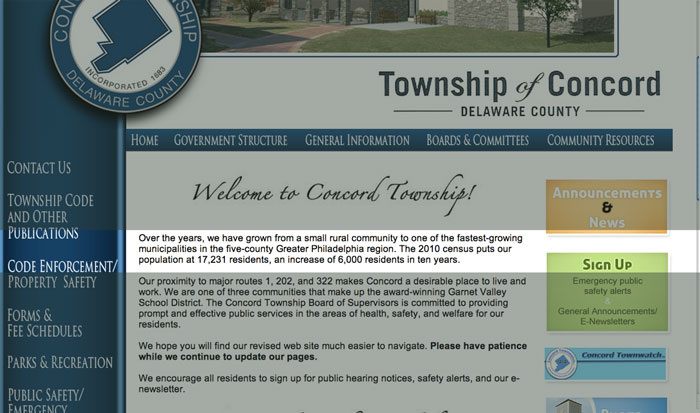

This ancient valley with its unspoiled meadows and rolling hills now stand in the way of a chain saw, a bulldozer, and a concrete truck. The fate of this amazing place hangs on a few short meetings of local politicians whose valuation of the land can be seen in the unprecedented development of Concord Township in the last 13 years, a once rural township which has grown from 10,000 residents in the year 2000 to 17,500 today. It is up to the 5 township supervisors to either accept or reject the rezoning proposal that would allow the developers to destroy the Valley. The Concord supervisors, however, have not had a history in favor of preservation.

Now a big question remains: If it's Woodlawn's land, don't they have a right to develop it if they so please?

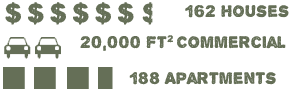

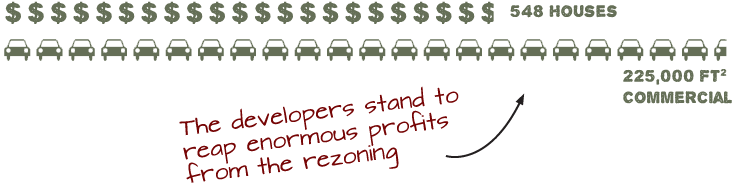

The answer is "YES*". They have a legal right to do some development, but they acquired the land through deceptive means, disguising their mission as a preservation organization while in fact their intentions were to develop. Legally, here's what they're allowed to build. This is known as the "By Right".

The By-Right

However, the developers are coming to the township and asking them to change the law so that they can build more houses and more commercial space. They are not even satisfied with what they can build by law. This is what they're proposing.

The Rezoning Proposal

The developers stand to reap enormous profits from the rezoning. This goes far beyond reasonable development. To get an idea of the density of development they're proposing, the following graphic illustrates is the difference between the current zoning and the rezoning proposal.

The developers stand to reap enormous profits from the rezoning. This goes far beyond reasonable development. To get an idea of the density of development they're proposing, the following graphic illustrates is the difference between the current zoning and the rezoning proposal.

Woodlawn has a contract with the developers so that if the rezoning is approved, they will sell the land to them. We want to oppose the rezoning so that we can then purchase the land, and donate it to the parks system so that it can be preserved forever. Remember, the developers are not legally entitled to the rezoning.

Let's take a look at the details of the rezoning proposal. On October 2, 2012 Concord Township Board of Supervisors held a rezoning hearing about this land. The purpose was to accommodate the desires of the four development parties:

- Wolfson (Commercial)

- McKee and Concord Homes (Residential)

- Eastern States Development (Active Adult)

- Woodlawn Trust (Seller of Wildlife Refuge)

The development proposals can be seen below.

Commercial

180,000 square foot big box store plus three smaller stores. 225,000 square feet in total.

Residential

314 dwelling units in duplexes and singles. This development is more dense than that allowed under current zoning.

Active Adult

120 active adult dwelling units in quads are proposed, 27.6% of the total 434 homes. National experience is that over time active adult homes become single family homes. This is important because single-family homes have children that "burden" the tax system by increasing the cost to the school district.

Existing Vineyard

The existing vineyard covers about 26 acres. Woodlawn included the vineyard in its common open space calculation. In reality, the vineyard is a commercial enterprise. Public access is largely limited by fencing.

Common Space

The remaining green pasture and forest would be common open space. This area includes wetlands, steep slopes, rare plants, rare animal habitat and trails. A deed restriction would be placed on the common open space, what little of it remains. Much of this deed restricted land would be inaccessible to the public.

Gas Pipeline

If the development is built as planned, the existing Colonial gas pipeline would pass under the big box store and between residential dwelling units. The pipeline carries refined liquid petroleum products, such as home heating oil, diesel, kerosene, aviation fuel, and gasoline. The 50 year old pipeline is 30-inches in diameter. You can read more about this in chapter L.

An Unfair Trade

Concord Township laws require that 40% of a parcel that is developed with five or more houses be maintained as open space. Other regulations limit building on steep slopes and in wetlands. The concord township supervisors and developers claim that we'll get more open space with the rezoning proposal than with the by-right. THIS IS NOT TRUE.

Let's take a closer look. Out of the 50 additional acres they give us in exchange for hundreds of additional houses, half of that land is the Penns Woods Winery which is an enclosed area that's not open to the public, and the other half are storm water retention basins and steep slopes. Neither of these can be regarded as true open space.

Our First Goal

Our first goal is to block the rezoning proposal that the developers submitted to the Concord board of supervisors. If that proposal succeeds we can expect drastic changes in our daily lives. In May, the developers withdrew their proposals in lieu of the opposition they were getting, but have every intention to resubmit once things settle down. We do not know when this date will be, but expect it will be soon after the election season in November.

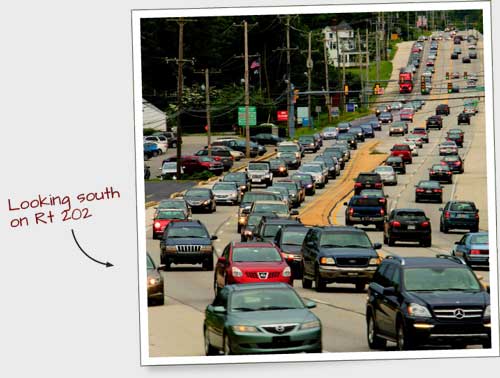

Traffic

The 202 corridor is already one of the most congested traffic corridors in PA. Our traffic studies suggest that if the rezoning proposal succeeds there will be upwards of 8,000-13,700 additional car trips on our roads evey single day.

Even with the by-right plan, traffic will increase by an additional 5,100 trips every day.

additional car trips

Our choices then are to have this horrific traffic, or to have 202 widened in order to accommodate it. Rather than pay for it themselves, the developers will pass this cost onto the Concord twp residents in the form of higher taxes.

Taxes

The township supervisors would say that this is going to be a boon for the school district. They've been saying it for years, but it never has been. Somehow the school district is $112 million in debt. In addition to paying for a road widening, Concord residents will have to pay an additional fire a police department - through their taxes. Have your taxes ever gone down after a development has been put in?

Our Wharton economist reported that due to the expensive infrastructure costs (widening of 202, sewer construction and maintenance, the likely need for a police force, increased demands on the fire department) taxes will definitely increase as a result. In exchange for this tax hike, Concord's last 3% of open space will be lost forever.

Our Wharton economist reported that due to the expensive infrastructure costs (widening of 202, sewer construction and maintenance, the likely need for a police force, increased demands on the fire department) taxes will definitely increase as a result. In exchange for this tax hike, Concord's last 3% of open space will be lost forever.

Ecologic Impact

The additional traffic resulting from either the rezoned development or the "by right" construction will have a significant environmental impact on Beaver Valley, the cost of which is not easily calculated. The increased pollution from thousands of additional cars will come in the form of increased air pollution as well as vast quantities of litter and automobile fluids, which represent a serious threat to water quality and wildlife. This marked increase in "non-point-source" pollution will degrade local streams and the Brandywine River. Oil, gasoline, lawn chemicals, pesticides, herbicides, windshield wiper fluid, and radiator coolant will flow downhill to the Brandywine River, which is a primary source of drinking water for the city of Wilmington. In addition to the residents of Wilmington, the untold thousands of species inhabiting the Brandywine and Beaver Valley Creek will all be subject to an increase of toxins in their environment.

Loss of Open Space

There are other costs, too, which are incalculable as in the loss of a beautiful viewshed, and the loss of "openness" that Beaver Valley provides. So what possible effect could all this have but to decrease the desirability of Concord as a place to live? What possible effect could this have but to hurt existing home values? What possible effect could all this have but to destroy one of the last places in Delaware County where you can hike without hearing a highway? Curiously, Concord Township's own open space report from the mid 90s describes the importance of maintaining open areas in their natural condition as something essential for residents and critical to maintaining real estate value. Only a handful of spaces remain that meet this requirement, and none of them come close in importance to Beaver Valley. There are those who say that anyone who opposes the "development" stands in the way of progress. This has always been the preferred attack on conservationists by industry groups seeking to exploit the land, timber, minerals, coal, uranium, oil, and natural gas from in and around the fifty-nine national parks. As the First State National Monument awaits Congressional designation as the 60th national park, the Delaware County portion could already be compromised.

Concord Township is one of the largest townships in the county, but it has no municipally maintained wooded trail systems. Its asphalt-covered trails lie under high tension wires, and much of its "open space" sits adjacent to very dense housing developments. Concord Township's website claims to support open space protection, and even celebrates the beautiful Woodlawn trails as something township residents should get out and enjoy. One would think this ready-made trail system would be acquired with the greatest possible dispatch by the township and the county. On the contrary, Concord Township supervisors have given no indication that they plan to save this land for future Concord and county residents. In a quintessential bait and switch, Beaver Valley is used to show how desirable the township is even as the supervisors cooperate with developers and Woodlawn to destroy it.

The threatened 324 acres was purchased from various landowners over the last sixty years by an organization called The Woodlawn Trustees whose original mission, as envisioned by its founder William Bancroft, was to protect open space for public recreation. That Woodlawn would sell this tract to developers is a betrayal of not only William Bancroft but those landowners from whom it originally purchased the various pieces of the tract. A DuPont chemist named Merlin Brubaker owned over 50 acres in Beaver Valley and wanted to have it protected. Turning down offers from real estate developers, he instead contacted the Woodlawn Trust in the late 1970s with the conservation of his estate in mind. Stephen Clark, at that time the president of Woodlawn, wrote to Brubaker thanking him for adding his land to that "which Woodlawn tries to protect." Consistently, many landowners along the PA/DE border were assured by Woodlawn that their land would be protected.

According to early Bancroft documents, the primary purpose of the Trust was to hold much of the land for the public. The greenway he envisioned offered the public an escape from the confines of the city. And Bancroft was not alone in wanting to save open space. 50 acres of the land scheduled for destruction in Concord Township was ironically sold to the Woodlawn Trust so that it could be protected. Merlin Brubaker was eager to protect his piece of Beaver Valley, so he contacted the Woodlawn Trust with the conservation of his property in mind. Exchanges between Brubaker and Woodlawn Trustees indicate a willingness to have the land protected for future generations. In this letter dated January 28th, 1981, Woodlawn president Stephen Clark closes his letter with, "a fine tract of land added to those which Woodlawn tries to protect." All throughout Beaver Valley and other parts of the Woodlawn Trust, land owners who sold to the Trust were similarly convinced that their land would be protected.

The Woodlawn Trustees would claim that the proceeds from their land sales are funneled into low income housing in Wilmington. This, they claim, is part of their dual mission. That opaque organization doesn't reveal the names of its board members, doesn't hold public meetings, and doesn't reveal publicly how its funds are disbursed. There's no way to know what the public gets for its loss of publicly used land. They would also proclaim that they pursue "orderly" development. Based on the large sell offs of their land over the last 60 years, this could only mean that they intend to pave over William Bancroft's legacy a little more slowly. Sometime in the 60s, the Woodlawn Trust began placing "wildlife refuge" signs around its land. These signs still dot the landscape, and indicate a motivation by the Trustees to protect the land for the wildlife that lives on it. Also in the 60's, Woodlawn incurred considerable expense to lay down a system of trails covering close to a thousand acres. What kind of a "trust" would sell off land that it went to the expense of building trails for? What kind of a trust would destroy habitat for wildlife after installing almost a thousand "wildlife refuge" signs? What kind of a wildlife refuge and publicly accessible recreation area covers its land with asphalt and concrete, cuts down its trees, and drives its wildlife away when for years it has signaled to the public that it wanted to protect the land? Interestingly, a document given to all lease holders and renters of Woodlawn Trust property in Beaver Valley and elsewhere also demonstrates a willingness to preserve and protect land for public enjoyment.

The Woodlawn Trustees would claim that the proceeds from their land sales are funneled into low income housing in Wilmington. This, they claim, is part of their dual mission. That opaque organization doesn't reveal the names of its board members, doesn't hold public meetings, and doesn't reveal publicly how its funds are disbursed. There's no way to know what the public gets for its loss of publicly used land. They would also proclaim that they pursue "orderly" development. Based on the large sell offs of their land over the last 60 years, this could only mean that they intend to pave over William Bancroft's legacy a little more slowly. Sometime in the 60s, the Woodlawn Trust began placing "wildlife refuge" signs around its land. These signs still dot the landscape, and indicate a motivation by the Trustees to protect the land for the wildlife that lives on it. Also in the 60's, Woodlawn incurred considerable expense to lay down a system of trails covering close to a thousand acres. What kind of a "trust" would sell off land that it went to the expense of building trails for? What kind of a trust would destroy habitat for wildlife after installing almost a thousand "wildlife refuge" signs? What kind of a wildlife refuge and publicly accessible recreation area covers its land with asphalt and concrete, cuts down its trees, and drives its wildlife away when for years it has signaled to the public that it wanted to protect the land? Interestingly, a document given to all lease holders and renters of Woodlawn Trust property in Beaver Valley and elsewhere also demonstrates a willingness to preserve and protect land for public enjoyment.

Regardless of Woodlawn's claims, it has evolved into a public trust due to the unfettered access they've granted the public for half a century. The wildlife refuge signs they posted and the trails they built in the 60s, the stewardship rules given to renters, and the letters from Woodlawn to potential sellers, all provide a glimpse of how Woodlawn once saw itself, as a Trust with protection of the land as a foremost consideration. What kind of an Orwellian caretaker designates a place as a wildlife refuge, builds trails for the public, tells its renters to be stewards and protectors of the land, and then destroys it?

Regardless of Woodlawn's claims, it has evolved into a public trust due to the unfettered access they've granted the public for half a century. The wildlife refuge signs they posted and the trails they built in the 60s, the stewardship rules given to renters, and the letters from Woodlawn to potential sellers, all provide a glimpse of how Woodlawn once saw itself, as a Trust with protection of the land as a foremost consideration. What kind of an Orwellian caretaker designates a place as a wildlife refuge, builds trails for the public, tells its renters to be stewards and protectors of the land, and then destroys it?

Almost with a guilty conscience, Woodlawn and the developers claim that their development will leave large areas of open space intact around the proposed development. But this red herring conceals the fact that much of their open space can't be developed anyway. For example, approximately 25 acres of the land that Woodlawn claims it is leaving as open space lies within the confines of the Penn's Wood's winery on Beaver Valley Road. No public trails will lie within its fenced-in vineyard. Much of the remaining open space acreage falls on steep slopes or wetlands.

Some say that private land owners should be able to do what they want with their land. We agree. William Bancroft, Merlin Brubaker, and Bill Derrickson intended to have their land protected. That's what they wanted to do with their land. The intent of these men seems not to matter as the Woodlawn Trustees, the developers, and the supervisors of Concord Township prepare to ignore the overwhelming opposition to this development.

A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing

A recurrent theme can be seen in the various documents relating to Woodlawn that have been uncovered. Avoiding tax liability comes up time and again. This is not something one would expect to find in the papers of a self-described benevolent organization like Woodlawn which publicly stated in an early press release that it "donated" 1,100 acres that would become the First State National Monument. Their preoccupation with avoiding taxes can perhaps better explain why instead of donating the land, Woodlawn transferred the 1,100 acres to Rockford Woodlawn, a non-profit entity entirely owned by Woodlawn Trustees, Inc. Rockford-Woodlawn then sold the 1,100 acres of its holdings for $21 million, or $19,000 per acre, to the Mount Cuba Foundation which turned around and donated it to The Conservation Trust, which then gave it to the federal government, putting the land on track to become Delaware's first national park. If, as Woodlawn publicly claims, it is in the open space business, then it either would have included the Beaver Valley tract along with the 1,100 acres, or it would have attempted to sell its Beaver Valley land in Concord twp and Wilmington, Delaware as open space at a price of $6.2 million, or $19,000 per acre.

As a not-for-profit, it has no share holders, but as the owner of 771 acres straddling the PA/DE border, it has plenty of stakeholders. For half a century, hundreds of thousands of hikers, bicyclists, and horseback riders have enjoyed the pristine landscape that William Bancroft and The Woodlawn Trustees originally strove to preserve. The past and present use of Beaver Valley matters not to the current board of trustees as they plan to carve up 324 acres of unspoiled beauty adjoining the First State National Monument and serve it up to developers. Delaware County would have the dubious claim of having a de facto National Park within its borders with no protective, undeveloped buffer around it.

The Concord Township supervisors are the ones in charge of ultimately accepting or rejecting the rezoning proposal in the Concord township portion of Beaver Valley. These supervisors have a history of voting in favor of development. Dozens of developments have been approved over the last 13 years, many of which have been approved over the strong objections of resident groups. The supervisors have run the township with little regard to citizen input. The new gargantuan sign on 202 is the latest example of this. Curiously, the supervisors rejected a similar sign along Route 1 near Newlin Grist Mill. This rejection was appealed all the way to Commonwealth Court in Pennsylvania, where it lost as well. Why the supervisors would reject a billboard in one part of the township, but approve a very similar one on the west side of the township remains an unanswered question. It could have to do with where in the township the supervisors live. Incidentally, the Lawyer representing the nationally opposed big box store proposed for Concord Township is Marc Kaplan who also represents the new billboard owner Thaddeus Bartkowksi.

Likewise, the supervisors have approved several unwelcome commercial properties over intense community opposition. These have increased the traffic load on township roads by several orders of magnitude. The supervisors have claimed that the commercial and residential development has benefitted the township and school district by increasing the tax base. The reality is that the various bonds the district has had to float to pay for school expansion has left the district 112 million dollars in debt. School district taxes have gone up exponentially over the last 13 years as a result of this unprecedented growth, something which the supervisors see as something to celebrate on the township's website. Concord township is the fastest growing municipality in Delaware County, at almost 50 times the county average. At this rate, if we haven't yet seen the benefits of development, we never will.

Three of the current supervisors have presided over the lion's share of this growth, which will ultimately negatively impact property values. As the township becomes increasingly crowded, Concord becomes a less desirable place to live. This will certainly prove true if they approve the developers' and Woodlawn's rezoning request.

There have been some rumblings that some of the supervisors may oppose the rezoning vote and force the developers to either work with what they are allowed "by right" to build, or walk away from the project altogether.

Kevin O'Donoghue and Libby Salvucci were quoted in the Delaware County Times as being in favor of opposing the rezoning proposal. Our fear though is that these off the record comments are campaign posturing, as Ms. Salvucci is up for re-election. In a widely circulated press release to reporters and political leaders in the township and county, we asked the supervisors to issue an unequivocal statement clearly indicating their intention to protect Beaver Valley. As of this writing, they have not done so.

Kevin O'Donoghue and Libby Salvucci were quoted in the Delaware County Times as being in favor of opposing the rezoning proposal. Our fear though is that these off the record comments are campaign posturing, as Ms. Salvucci is up for re-election. In a widely circulated press release to reporters and political leaders in the township and county, we asked the supervisors to issue an unequivocal statement clearly indicating their intention to protect Beaver Valley. As of this writing, they have not done so.

It has been argued that the supervisors have greenwashed Concord residents regarding their open space protection efforts. Various parcels in the township that they claim to have "protected" are either inaccessible to residents, are "posted" with "keep out" signs, or possess very little value as real open space. For example, the township park on Smithbridge Road behind the Rachel Kohl library is proudly touted as open space. The park, though, is visually marred by unsightly PECO high tension lines. Moreover, the sterile playing field is not conducive to supporting wildlife. Other so-called open space parcels fall completely within PECO right-of-way, complete with security gates and keep out signs. Meanwhile, the Board of Supervisors' open space committee liaison, Dominic Cappelli, recused himself from the rezoning vote. The supervisors are staring at the most beautiful piece of open space in our township, and seem very much inclined to vote to destroy it.

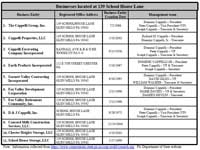

In addition to demonstrating a disdain for community input, two of the supervisors in particular have shown a disdain for zoning law even as they stand ready to approve an outrageous change in Concord zoning. For years, Dominic Cappelli operated a heavy commercial business in a residential neighborhood on School House Lane. Many local Concord residents along School House Lane and Andrien Road opposed this violation of zoning law, taking their case to court. After a lengthy legal fight, a state appellate court issued an order to cease commercial operations on School House Lane. For years, the Concord supervisors ignored the order issued by Judge Doyle and allowed commercial operations to continue in a residential neighborhood. All the while, Dominic Cappelli sat on the Board of Supervisors.

Although Dominic Cappelli has recused himself from the rezoning vote, he refuses to state why. A reasonable person can be forgiven for assuming that Cappelli plans to profit from construction in Beaver Valley. Even though he can't vote on this issue, he maintains influence over the other supervisors.

Call a supervisor and tell them that you DO NOT APPROVE of construction on the 325 acres in Beaver Valley. Let us know in the question box below when you made a call! Please be courteous!

Dominic A. Pileggi - 610-459-3302

John J. Gillespie - 610-361-0566

Dominic J. Cappelli, Jr. - 484-840-0947

Kevin P. O'Donoghue - 610-459-5656

Elizabeth "Libby" Salvucci - 610-361-0503

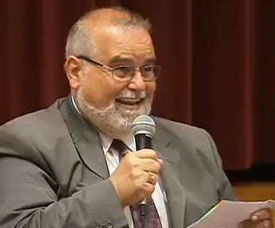

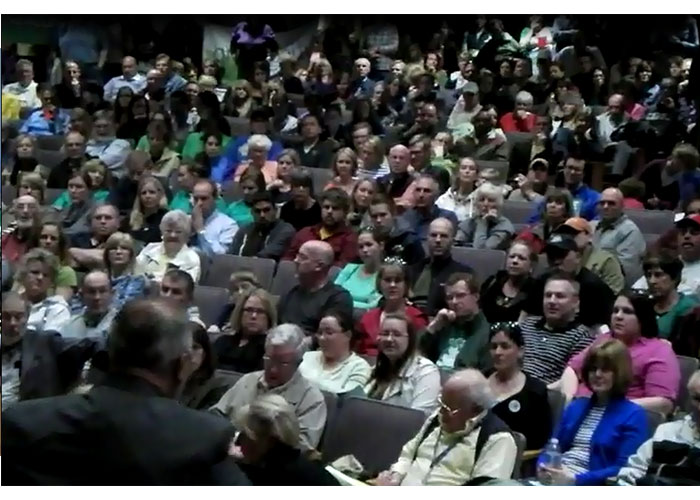

The supervisors have made many decisions without regard to citizen input even though these decisions directly impact residents in the township.The frustration resulting from this in large part has helped to galvanize opposition to the development plans in Beaver Valley. When Save The Valley and other groups went door to door in Concord in early May alerting residents to the planned destruction of this beautiful place, positive responses were overwhelming. As a result, upwards of one thousand people turned up at the May 14th rezoning hearing at Garnet Valley Middle School to show their opposition to the proposal.

Our movement has grown increasingly stronger with each passing month. Since the May meeting, we have added hundreds of names to our contact list, which now rivals the circulation of several area newspapers. In addition, the SaveTheValley facebook page has surpassed 3,500 supporters as of this writing.

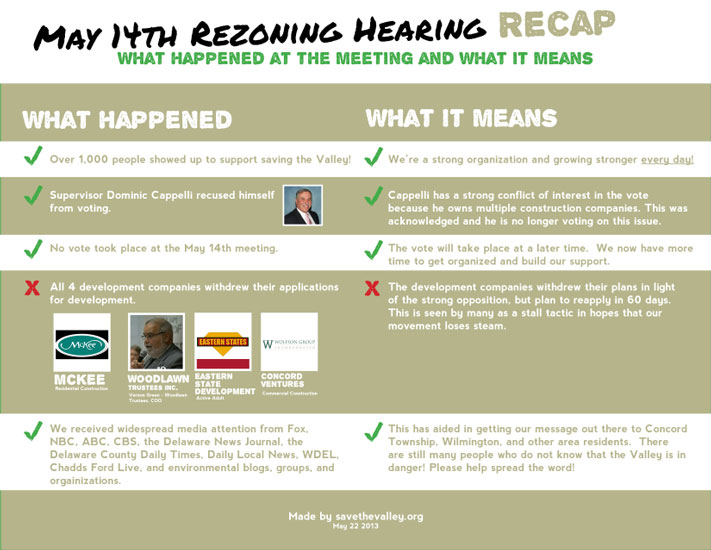

On May 14th, 2013, there was a planned assembly in order to address the rezoning proposal by the developers. This type of meeting is called a "rezoning hearing meeting." The township expected a meager turnout, but we knew we could rally the masses. We submitted a "change of venue" request so that we could accomodate all of our supporters.

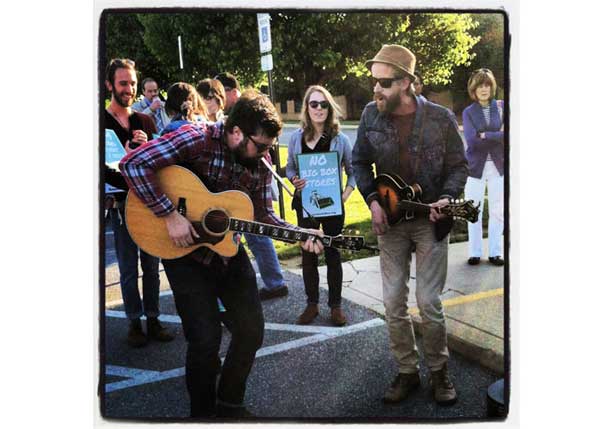

The hearing took place at the Garnet Valley Middle School auditorium, and turned out almost a thousand people. There were pickets and petitions in protest, public displays, and protest songs. Right before the start of the meeting we were informed that all four developers withdrew their proposals.

Don't get your hope up though, they have every intention of reapplying, and will probably do so shortly after elections in November.

Here's the outcome of the rezoning hearing:

On August 10th, 2013, three organizations came together to celebrate open space at the Newlin Grist Mill with the first annual Open Space Music Fest. There was great music from 10 different bands, craft beer from Victory Brewing, and food from Pizza Wagon and Shoo Mamas. For the kids, there were pony rides, face painting, and colonial-era games including Native American spear throwing.

On August 10th, 2013, three organizations came together to celebrate open space at the Newlin Grist Mill with the first annual Open Space Music Fest. There was great music from 10 different bands, craft beer from Victory Brewing, and food from Pizza Wagon and Shoo Mamas. For the kids, there were pony rides, face painting, and colonial-era games including Native American spear throwing.

We had an amazing turnout, and created an invaluable community event where people could enjoy music outdoors. Visit openspacemusic.org for more information about the event.

Events

Open Space Music Fest

Beef & Brew

New Events for 2013/14

Presentations/Public Outreach

Maris Grove

Walker Street

Postcards and mailings

Press Releases

Alerts

(Alerts are concise documents presenting research data on the impacts of development in Beaver Valley. These can be found in Chapter L.)

- Rezoning - posted to web

- Pipeline - posted to web

- Ecology - drafted

- Open space

- Economics

- History

Facebook Supporters

Petition Signatures

Videos Views

Visitors to Our Website

Movies

Movies